Design meets circus: How creative problem-solving and experience-driven design elevated an aerial acrobatics performance

Or, the story of how I started something before I felt ready, and how I used my design skills to save myself from shame.

Experience-driven designProblem-solvingDesign processExperience evaluation

Introduction

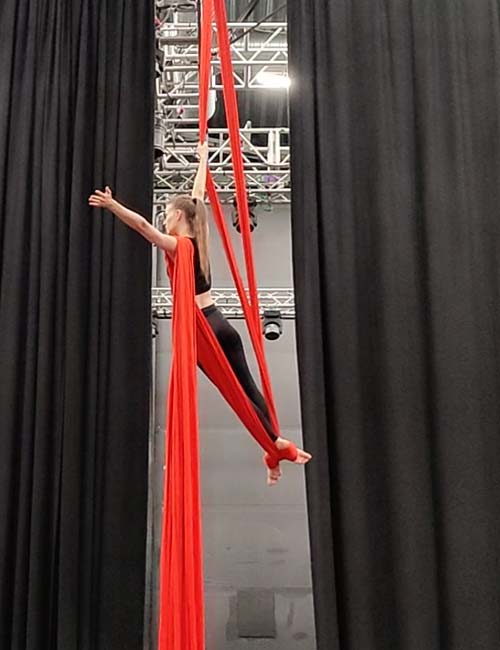

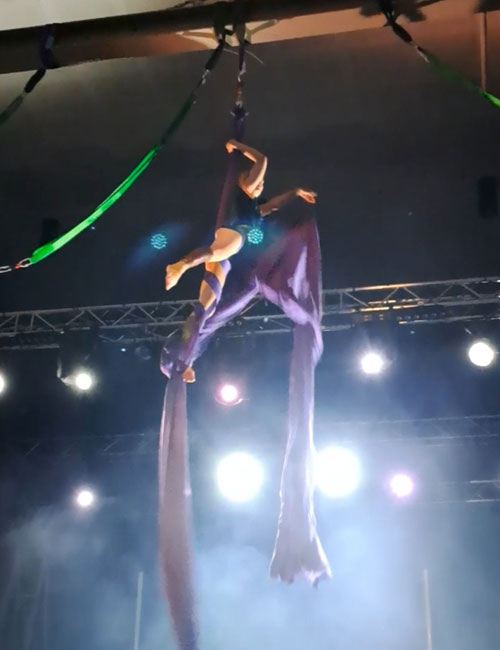

This case study tells the story of my very first solo aerial performance—and my first time creating choreography entirely on my own. Rather than approach it only as an artistic challenge, I decided to frame it as a design project. By applying creative design methods and the principles of experience-driven design, I set out to create an aerial acrobatics performance that would deliver a meaningful experience for both myself and the audience. This project spanned almost six months from sign‑up to stage: I registered for the Aerial Arts Showcase in spring, trained through the summer and autumn, and finally performed at the event in November 2022.

Problem statement

The challenge could be divided into three parts:

- Plan and practise a choreography—an obvious requirement of participating in a showcase event, but worth making explicit.

- Express the theme defined by the event organisers.

- Produce a certain type of experience for the audience. This was my own addition, turning the project into an experiment in applying design methods to aerial arts.

The first two were external requirements set by the event. The third was self-imposed, and it became central to how I approached the process.

Target audience

Aerial Arts Showcase is an event for aerial and pole enthusiasts, so most of the audience were amateurs or professionals already somewhat familiar with the art form, along with their friends and families. This meant that many people in the audience would have informed opinions about difficulty, execution, and impressiveness—more so than an audience with no prior exposure.

In addition, I planned to perform the same choreography later at Studio Move’s open stage, where the audience could also include practitioners of other dance styles. Beyond live audiences, I also expected my friends and acquaintances to see the recorded performance online.

Scope and constraints

The event had categories based on apparatus, and since I only train on aerial silks, the choice was clear.

My training was limited by access to space: the studio most available to me had a ceiling height of only four metres, while the showcase rigging reached seven. I therefore had to choreograph for four metres but still test at full height to avoid stage shock.

Physical limitations also shaped my choices. For example, with an inflexible spine, I excluded backbends that I knew would not appear convincing on stage.

Process

The guiding principle of my process was experience-driven design, a concept familiar from user experience design. Its core idea is simple: the product is a means to an end, and the true goal is to enable a particular experience. In this case, the “product” was already fixed—an aerial acrobatics performance—so I couldn’t follow the approach in its purest form, where the outcome is not yet known. Still, I used the method to frame my decisions.

Experience itself cannot be designed, as it is always subjective. What can be designed are the conditions that make certain experiences more likely. I therefore set clear experience goals and evaluated each choice against whether it supported them.

For readers interested in the background of this approach, see:

Hassenzahl, M. (2010). Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 3(1), 1–95

Theme selection

The 2022 Aerial Arts Showcase was built around the theme Immortals. Each performer had to choose one theme of four options drawn from Greek mythology:

- Hecate – witchcraft, the afterlife, and the Moon

- Alke – bravery and perseverance on the battlefield, the divinity of survivors

- Chaos – destruction and disorder, but also the beginning of all life

- Nemesis – revenge, justice, and getting what you deserve.

To explore the options, I used a writing exercise: for each theme I reserved a page and listed what kinds of tricks and movement styles could represent it—and just as importantly, what would not.

For example, for Hecate I imagined complex wrappings on silks to resemble magical runes, or highly flexible shapes. Since extreme flexibility is not my strength, I ruled it out early.

In the end, I selected Alke, the spirit of courage and perseverance. Its description resonated with the kind of story I wanted to tell, and it also aligned with some promising song choices I had in mind.

Music selection

Although the event allowed much more time for choosing music than for choosing the theme, I made both decisions together and committed to them from the start. I wanted a song that would:

- Complement the choreography

- Support the chosen theme

- Move me emotionally so I could practise to it endlessly.

After trying and abandoning an early option that proved too fast, I systematically searched Spotify for something both dramatic and manageable. Eventually I found Raise Your Flag by Hidden Citizens (feat. Rånya). It had the right tempo, intensity, and a convenient length of 3:42.

The only compromise was its fading ending, whereas I had hoped for a striking finale. I chose to adapt the choreography rather than alter the music.

First demo test

At the beginning of August I recorded a demo video of about a minute and a half, showing the opening of my choreography with the chosen music and movement style. I then asked seven people to watch it and guess which of the four themes it represented—four were from aerial and pole circles, three were laypeople.

Results: four guessed Alke, one guessed Chaos but added “if it’s not that, it’s Alke,” and two could not decide. Correct guesses did not align with whether the person practised aerial arts or not.

Since more than half identified the theme even without costume or expression, I felt confident to continue on this path.

Experience goals

In addition to expressing the theme, I wanted to set clear goals for the kind of emotional response my performance might evoke in the audience. This was where I leaned most on experience-driven design.

I knew I could not impress with extreme flexibility or the most technical tricks. Instead, I chose to focus on an engaging overall performance, with storytelling at its core. The story should be easy to follow, dramatic and entertaining—more like a Disney film than an abstract artwork.

To compensate for less showy tricks, I aimed to use expression and drama. This meant pushing myself outside my comfort zone: learning to use facial expressions, gestures, and body language to bring the story to life.

I set the following experience goals:

- Inspire viewers who recognise the difficulty and flaws but have never performed themselves, leaving them with the feeling that they too could shine on stage.

- Draw viewers in so they lean forward—literally or metaphorically—and feel that they are part of the story as I address them directly.

In other words: on stage, I am Alke—a mythical character who encourages and inspires perseverance, and instils fighting spirit into an audience that becomes the army.

For this vision, the chosen song also offered excellent material, especially with two repeated verses: “…and we have arrived” and the most memorable part: “this is our time!”

Journey mapping

Are you even a designer if you don't use a journey map?

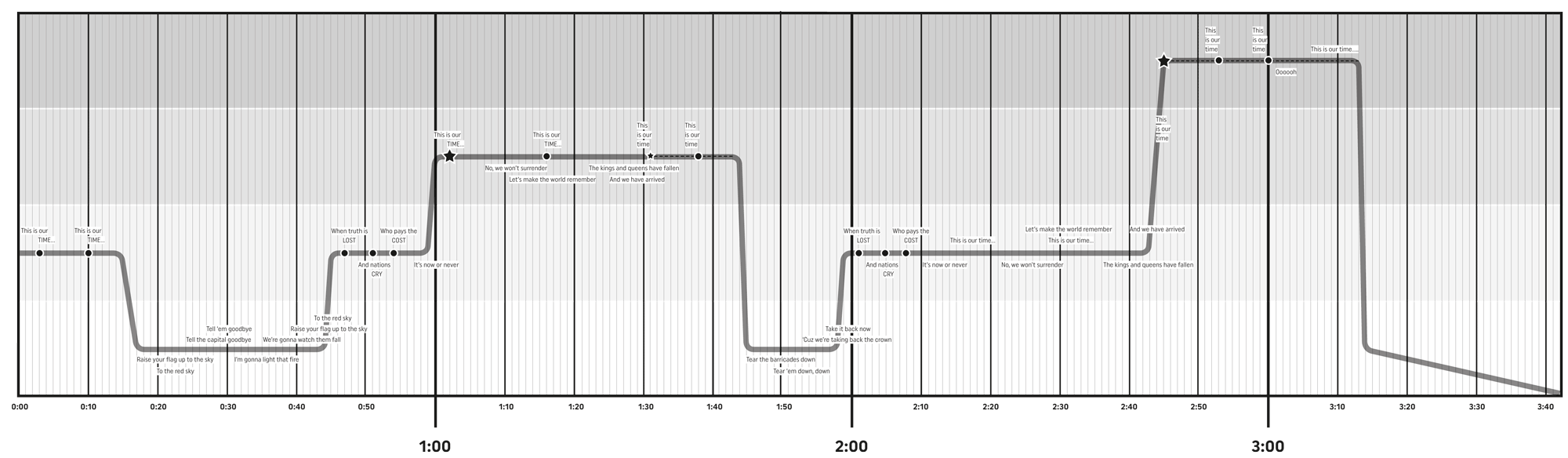

Early in the process, I analysed my chosen song and drew a map of it as a template for choreography planning.

This helped in several ways:

- I could see the exact timing of the song without replaying sections.

- I divided the song into sections, noting how the drama rose and fell to guide the overall arc.

- I marked significant beats in the song—circles for optional movements, stars for places where something spectacular had to happen.

The map was useful both in the studio and at home: I could plan sequences and test whether a trick might fit a certain beat, even without training space. Most of these calculations were based on video clips of individual tricks I had already recorded.

Selection of tricks

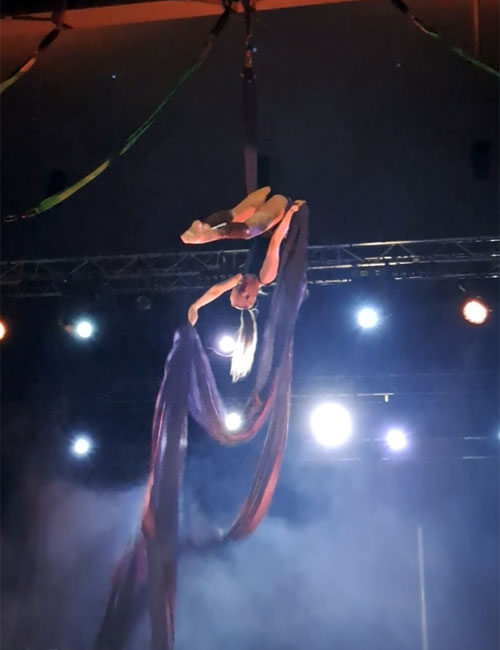

The theme I chose, Alke, represents courage and perseverance. Since the song could be read as a battle story, I aimed for strong, powerful movement language. To show perseverance, I also included “setbacks” – tricks that look like accidents but are recovered from during the choreography.

All tricks were selected against these criteria, though some transitions were necessary evils with less narrative weight. One example was spinning: because the rigging included a swivel, I needed to generate spin myself. Adding spins ensured movements were visible from all angles—but the spinning itself carried no symbolic role.

Some moves changed when I reconsidered their fit with the theme. In my first demo I began in a crouched, closed position high on the silks. One respondent interpreted it as sadness and loss, which didn’t match courage. I revised it into a standing lean, more like guiding others than dwelling on my fate.

My final pose, the Iron T, also needed adjustments. The song ends quietly, but the static hold requires strength. At first I moved my legs as if running in the air; however, I realised that if my spin had stopped and I faced away from the audience, it could look like I was running away. With feedback from my coach and a fellow aerialist, I replaced this with two distinct leg positions before the final pose with legs tightly together—so the divinity of survivors would not appear to flee. (In the end my back did face the audience, just as I had feared, so it was fortunate I had made these changes.)

Performance outfit

For the performance, I needed an outfit that both fit the theme and met the practical demands of aerial acrobatics:

- Easy and comfortable to move in.

- Able to withstand extreme positions, sudden movements, and apparatus contact without risk of revealing too much skin.

- No hard or sharp parts that could damage the fabric apparatus.

- No loose fabric that could get caught and tear (I have ruined shirts this way).

Within these limits, I wanted a subtle reference to Ancient Greek warriors—something recognisable on stage but not a cheap costume. Cloaks or skirts were out for safety reasons. I asked my coach, who also designed and sewed the costume, to keep the warrior reference subtle.

Because details might get lost in lighting or tangled with the silks, I dreamed of adding a headpiece reminiscent of a Greek helmet. It too had strict requirements:

- Stay secure even when upside down.

- No hard or sharp parts that could damage the apparatus.

- Safe for me—no chin straps or dangerous fastenings.

I had no clear attachment method in mind when I began prototyping with plain paper. My goal was a quick Minimum Viable Product: something cheap, durable enough for a few shows, and convincing in stage lighting.

The final version, made of EVA foam, was shaped into a helmet framing my face. It was glued and sewn together, held on by a rubber band around my head secured with hair clips under the visor, and the cheek pieces fixed with clothing tape. The homemade “helmet” met all functional criteria and stayed securely on through every performance.

Storytelling through detail

Throughout the process, I kept asking myself how to better sync my movements with the music and connect the choreography to the lyrics. I knew the audience would see the performance only once and might not notice every detail, but I wanted to build layers for those who did.

From the start, I aimed for more than a string of tricks set to music. I wanted a coherent whole, using immersion to compensate for fewer show-stopping moves.

With that in mind, I planned moments of apparent eye contact to draw the audience in. Timed to the lyrics “and we have arrived” and reinforced with hand gestures, these cues may seem simple, even clichéd, but they supported my goal of creating an entertaining and emotionally engaging show. Similar gestures underlined “this is our time,” with my gaze following where my hand pointed.

I also played with the silks themselves. For the lines “We’re gonna watch them fall” and “the kings and queens have fallen,” I held the long tail on my shoulder, then let it drop in time with the lyrics. Some rehearsal viewers noticed the theatricality of the move, though it was unclear if they caught the lyrical connection.

Performances

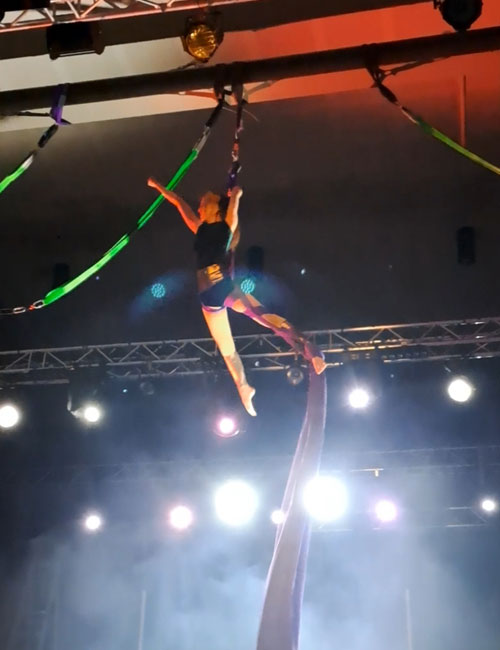

I presented the choreography twice: first at Aerial Arts Showcase in Helsinki, and later at Studio Move Open Stage in Tampere. Only the Helsinki performance was recorded, with stronger stage conditions and lighting.

Judges' feedback

At Aerial Arts Showcase, each performer received short written feedback from the judges. The notes focused on what stood out most, rather than a full critique. With six judges—all professionals or semi‑professionals in pole or aerial arts—the comments provide a useful lens for evaluating whether I met my goals.

- “The costume suited the theme very well, the drop sequence was beautifully timed with the music, and the audience contact was ++. The ending was lovely!”

- “Dramatic performer, good strong and calm audience contact, musical and dynamic choreography.”

- “Wonderful expression and good stops and poses.”

- “Still need a bit more calmness in the execution, although the song and interpretation were strong, still some calmness in super gorgeous moves <3”

- “Immersive performer, strong gaze, great silhouettes.”

- “Stunning costume!”

Based on the comments, I succeeded in expression, drama, and audience contact—my main goals. The note about calmness is a fair critique of the technical execution, and achieving it would not diminish the intended drama.

Although the costume was praised twice, with one judge noting its fit to the theme, none specifically remarked on whether the tricks, music, or story succeeded in conveying it. This leaves it unclear how well those elements supported the theme from the judges’ perspective.

Evaluation of the audience experience

Since I had defined goals for the audience’s experience, I wanted to evaluate it. The simplest method was an online survey, which I kept short: a few background questions plus two open ones:

- What was the most memorable thing about the performance for you?

- Describe the feelings that the performance evoked in you.

I avoided closed questions, as they might steer answers. I shared the survey on my own social media after my second performance, so most respondents had either seen the video or the later open stage show.

Nine people replied. While I cannot know exactly who they were, they likely knew me in some way. Still, it is unlikely they were my closest family, whose feedback would be uncritically positive. Their viewing contexts were:

- Four saw the performance at Studio Move’s open stage

- Four watched the video from Aerial Arts Showcase

- One saw the performance live at Aerial Arts Showcase.

Five respondents practised aerial arts, four did not (laypeople). I considered these groups separately in my analysis.

In the responses, four practitioners highlighted immersion, body language, or attitude as the most memorable aspects of the performance. Three laypeople instead noted impressive movements, with some adding how well they matched the music:

- “Impressive movements that emphasised the high points of the music.”

- “I particularly liked the movements and accents that matched the rhythm.”

The difference between the responses of practitioners and those of non‑practitioners is interesting but not surprising. My choreography was not particularly difficult, and those with aerial experience could likely imagine doing the moves themselves. Immersion, however, is a separate skill that is not usually practised in ordinary training.

When asked about the emotions the performance evoked, responses did not differ much between the groups or between live and recorded viewing. Most mentioned admiration or simply “wow.” Two described stronger reactions:

- “I may have become a little emotional” (saw the performance live)

- “I got chills watching this.” (saw the performance on video)

One answer came closest to my intended impact: “I am really bad at analysing things like this, but the performance felt uplifting, energising.” This suggests my character did create a connection, supported by other mentions of being “excited” or “interested.”

Music was also repeatedly mentioned, which was rewarding given how carefully I chose it:

- “Of course, the music was really powerful in creating the atmosphere, and together with the performance, it was a strong combination.”

- “The music choice fit perfectly with this.”

- “I personally wouldn't listen to that song alone, but together with the performance, it was also great.”

One respondent mentioned rewatching the video several times, and I received similar comments on social media. Such reactions felt rewarding after all the effort.

Outcome

The result was the culmination of nearly six months of planning and practice: an aerial acrobatics performance on the theme of Alke, the embodiment of fighting spirit from Ancient Greek mythology. In addition to two live shows, many people saw the video, and a few even witnessed rehearsals.

My primary goal was to create a powerful experience for the audience, though the process was also new and meaningful for me. I did not want to choreograph only for myself, so I defined experience goals and designed the piece with them in mind.

I evaluated the outcome through survey responses and informal feedback. To some extent I succeeded in creating a memorable, emotionally engaging performance. The responses also suggest I achieved the specific experience I aimed for, though with so few answers I cannot be certain it matched my vision exactly. Experiences are always subjective, and success can never be guaranteed. Still, I count it a success that the performance evoked emotions and left an impression.

Limitations

From a systematic design and experience evaluation perspective, the process had shortcomings. I could have gathered more survey responses by communicating the need for feedback more actively, or by requesting input directly from the Aerial Arts Showcase audience. That would have offered insights from people unfamiliar with me and allowed comparison between audiences who knew the performer and those who did not.

Involving more outsiders earlier, as I did in the demo stage, might also have strengthened the evaluation. However, I chose not to ask my close circle for continuous feedback, and I preferred that most people experience the performance only in its final form. The feedback might have been different if people had seen several rehearsal versions instead of only the final performance.

Lessons learnt

The biggest lesson was simply that I can do this. Success required systematic, persistent work—I was far from motivated all the time. To keep moving, I set fixed times for gym sessions and choreography practice, whether I felt like it or not. In the early stages frustration was strong, but repeating the mantra trust the process kept me going. Once all the tricks were chosen and training turned into full run-throughs, the process felt easier—or at least different.

If I were to start again, I would probably do many things the same way. I might seek opinions more often when deciding between trick options, but the main criterion would still be artistic fit rather than subjective impressiveness.

Here are some tips for planning a choreography from the perspective of a designer—not a professional choreographer:

- Define your goal. Adjectives are often easiest, but full sentences work too. Even with a classic dramatic arc, think about the emotional states along the way.

- Analyse what movement language and tricks best express that goal. Also note which do not.

- Write it down. Writing is thinking, and it helps to work on ideas outside the training space.

- Kill your darlings. Don’t force tricks into places where they don’t belong. Stick to what supports your goal.

- Ask for feedback in a way that links to your goals. For example, ask viewers to guess what you are expressing, or which trick best fits the intent—not just which looks “coolest.”

- Accept that there is no perfect creative process. You will have to make compromises and move forward even while uncertain. Don't stress about following the above guidelines. Only safety rules are strict; creativity is not.

Thanks

I also received invaluable help along the way, without which I might not have made it to the finish line. I want to thank my coach Sini-Susanna Paavilainen, who not only helped with improving the technical performance but also sewed my performance costume; Iina Peritalo for the conditioning exercises that supported the sport-specific training; and Vilma Lepistö for sharing the whole journey as important peer support. In addition, thanks to everyone else who gave feedback along the way. And finally, thank you to the awesome audiences and everyone who watched the video—you made it possible for me to have a fantastic experience from the performance as well.