Introduction

Problem statement

The challenge can be divided into a few parts:

- Plan and practise a choreography that:

- ...expresses the theme defined by the event

- ...and produces a certain type of experience for the audience.

Target audience

Aerial Arts Showcase is an aerial acrobatics and pole dance event, so in practice, a large part of the audience consists of amateurs and professionals who are more or less familiar with the subject matter, as well as their friends and family.

In addition, I planned to perform my choreography later at my own hobby studio, Studio Move's open stage, where there may also be practitioners of other dance styles in the audience. Of course, I also wanted my friends and acquaintances to see at least a video of my performance. However, I could assume that a large part of the audience understands something about acrobatic sports, so they have stronger opinions than laypeople, for example, on the impressiveness and difficulty of the tricks.

Scope and constraints

The event had categories based on the apparatus used, and since I only train with one type, the choice was clear: I would perform on aerial silks.

The time spent on training was limited by, among other things, getting free training times in a suitable space. In addition, the only training space that was somewhat regularly available had a ceiling height of only about four metres, while the aerial silks on the event stage were rigged at a height of about seven metres. I had to design my choreography so that I could perform it entirely in a four-metre space, but on the other hand, I had to try it out a few times in a higher space so that I would not panic during the actual performance.

My own physical limitations affected the choice of tricks included in the choreography. For example, I have an inflexible spine, so I did not want to include backbends in the choreography because I knew I could not make them look impressive.

Process

The guiding principle of my creative process was Experience-driven design, a design approach familiar from user experience design. In essence, the goal is to create a certain experience, and the designed product is a tool that helps bring about the experience. In this case, as is often the case in practical design work, it was not possible to follow the principle strictly, as the “product” was already defined: the end result of the creative process was to be an aerial acrobatics performance. In truly experience-driven design, the end result is not yet known at the outset.

Experience is always subjective and cannot be designed. However, it is possible to design and shape all the elements that enable the desired experience. Even this task allowed me to aim for a certain, precisely defined experience and make choices based on whether they helped me achieve my goal.

For those interested in experience-driven design, I warmly recommend this book:

Hassenzahl, M. (2010). Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 3(1), 1–95.

Theme selection

The theme for the 2022 Aerial Arts Showcase was Immortals, based on the characters from Ancient Greek mythology. The adult showcase had four themes to choose from, regardless of the apparatus. The given themes were:

- Hecate: representing witchcraft, the afterlife, and the Moon

- Alke: representing bravery and perseverance on the battlefield, the divinity of survivors

- Chaos: representing chaos and destruction, but also the beginning of all life

- Nemesis: representing revenge, justice, and getting what you deserve.

The theme selection process began with a writing exercise. For each theme option, I reserved a page to write down thoughts on what types of tricks and movements could represent each theme, as well as what would NOT represent them.

For example, for Hecate, the performer could use complex wrappings on aerial silks that resemble mystical writing or magical runes, or unnatural flexibility moves. However, since the latter did not belong to my strengths, Hecate was ruled out as an option early on.

The selected theme had to be communicated to the event organisers by the end of July. I made the final decision independently without consulting anyone else. In addition to the analysis, my choice of theme was also influenced by the interesting song options I had in mind for each one.

Music selection

The performance music for the choreography was supposed to be announced to the event organisers in October, but I locked in my selection along with the theme choice. I considered the selection important for three reasons:

- I wanted the song and choreography to seamlessly complement each other

- I wanted the song to support the chosen theme

- I wanted the song to have an emotional impact on me as well, to inspire me and so that I would be able to listen to it again and again during the upcoming months of training.

In addition to analysing themes, I wrote down different music options that I had in mind for each theme.

The first option was in my mind already in early summer, but I abandoned it after the first improvised experiments. The tempo of the song was fast enough that the risk of not being able to make the end result really smooth to the beat of the music was too great. Disappointed, I gave up on the idea that I had already envisioned well into the execution.

Finally, I systematically searched for potential songs on Spotify by listening to artists I didn't know before, but whose genre was appropriate. There was a phase where I didn't find anything that felt good, but eventually I found an inspiring song that supported the theme Alke: Raise Your Flag by the Hidden Citizens collective, sung by artist Rånya.

The song was almost everything I hoped for: a suitable tempo that would not make the choreography an excessively strenuous aerobic performance; dramatic enough to make the performance interesting enough; and a suitable length of 3:42 so it was not necessary to shorten or lengthen it.

I had to settle for only one compromise: the song fades out to a calm end, although I had dreamed of a strong, striking ending that could have been combined with a spectacular finishing move. However, I was content with this, as I did not want to radically edit the song.

First demo test

At the beginning of August, after the theme had already been decided, I shot a demo video of a little over a minute and a half showcasing my first ideas. The video featured the beginning of my choreography, performed to the chosen music, using the movement language I had chosen.

My intention was to show the video to a few people and ask them to guess which of the four theme options was being represented. I showed the video to a total of seven people, four of whom were from the aerial acrobatics and pole dance circles, and three who were completely unfamiliar with these activities, i.e. laypeople.

Of the seven testers, four primarily guessed that the chosen theme was Alke. One person guessed Chaos, but added that “if it's not that, it's Alke.” Two people were unable to make a clear choice, as they saw many options in the demo. The correct guesses did not correlate with the testers' background in these activities.

Because more than half of the guesses were correct based on the first demo, which lacked expression and a suitable costume for the theme, I felt confident in continuing along the chosen path.

Experience goals

I wanted to utilise Experience-driven design when approaching the design challenge. Along with defining the boundaries for expressing the theme, I wanted to set goals for the emotional response or reaction I hoped to elicit in the audience.

Knowing my own strengths, I knew I could not impress the audience with extreme flexibility or highly technical movements that professionals in the field often do. Instead, I chose to focus on creating an interesting overall performance, with storytelling playing a key role.

The story should be easily comprehensible in a popular way—the aim was rather to create a dramatic and impressive entertainment experience, similar to a Disney movie, rather than a work of art dealing with abstract concepts.

What I lack in the impressiveness of my tricks, I could try to compensate for with emotional expression and drama. Even in these areas, I would be well outside my comfort zone, but I could learn facial expressions, gestures, and body language to better convey the story and appeal to emotions.

I set the following experience goals:

- I want to inspire those viewers who can recognise the difficulty level and potential technical flaws in my performance, but who have not yet done anything similar themselves, and give them a feeling that maybe they too could shine on stage.

- I want to make the viewers (metaphorically or literally) lean forward in their seats and feel that they are part of the story, and I specifically address them.

In other words: on stage, I am Alke—a mythical character who encourages and inspires perseverance, and instils fighting spirit into an audience that is the army.

For this vision, the chosen song also offered excellent material, especially with two repeated verses: “...and we have arrived” and the most memorable part: “this is our time!”

Journey mapping

Are you even a designer if you don't use a journey map?

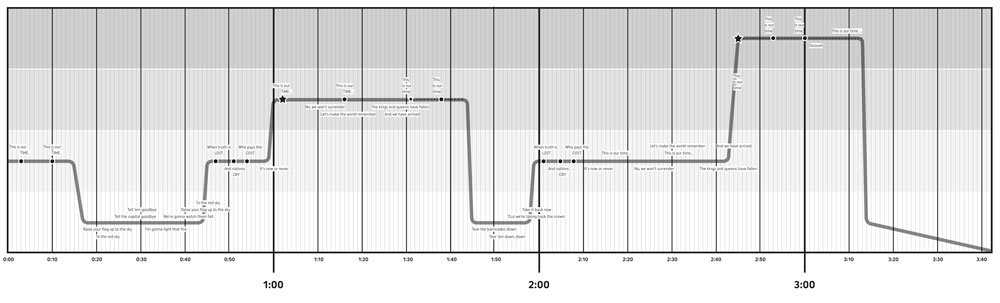

In the early stages of the process, I also analysed my chosen song and drew a map of it, which was intended to serve as a note-taking template for choreography planning.

Drawing the song as a map helped in many ways:

- Documentation of the timing of the song: I knew exactly when in the piece things were happening, without having to search for specific parts by listening again.

- My interpretation of the structure of the song: I divided (with my arbitrary interpretation) the piece into sections and assessed their level of drama in relation to each other to plan the whole, taking these changes into account.

- Documentation and interpretation of important parts of the song: I marked significant beats in the piece with either a circle (= “do some movement here if possible”) or a star (= “a spectacular movement must be done here”).

The map was helpful both in the studio while training and especially at home: I could plan and process my choreography even when I couldn't try if, for example, a certain movement could be timed to fit after a particular move and still hit the desired beat. I mostly made calculations based on individual tricks from the videos I shot.

Selection of tricks

The theme I chose, Alke, represents courage and perseverance. Therefore, because the story of the song can be interpreted as taking place in some kind of battle, I wanted the movement language to be strong and powerful. Additionally, I wanted to express perseverance through “setbacks”—in other words, tricks that appear to be accidents but are recovered from during the choreography.

In general, all the tricks that were included in the choreography were chosen based on whether they met the criteria I had set. The connection to the story and goals may not be immediately apparent for every choice, as some transitions and actions are mostly necessary evils.

An example of such a necessary evil is spinning on the aerial silks. As the apparatus was attached to a ceiling beam, it was not possible to move it with the help of an assistant. The rigging included a swivel, which allows the apparatus to spin 360 degrees (around the y-axis), but the spin is only produced by the performer's movement. Spinning the tail of the silks to gain momentum for revolving is not necessary, but it is desirable from both the performer's and the audience's perspective: if the apparatus does not spin, the performer can't ensure that the movements are visible at an appropriate angle to the audience. In my own choreography, there were a total of four spots for gaining spinning momentum that did not have a narrative role.

Some moves changed along the way when I questioned their suitability to the theme. For example, in my first demo, I started the performance in a crouched position up high on the apparatus, with my chin tucked into my chest. When the music started, I straightened my legs and leaned back, then returned to the crouched position to take momentum for spinning. One respondent who tried to guess the theme interpreted this part as expressing sadness and loss, among other things. I also began to question why an embodiment of courage would be in a closed crouched position. I changed the move so that I remained standing and leaned to the side, to seem more like I am guiding others rather than dwelling on my fate.

Similarly, my final pose, the Iron T, was subjected to critical examination. As I explained when choosing the music, the song ends peacefully, but the chosen final position is a static hold that requires upper body strength. In the early stages, I moved my legs during the pose, as if I were running slowly in the air. At some point, I realised that my spin momentum had likely dissipated by the end pose, so I might be at any angle to the audience. If this angle happened to be facing away from the audience, I would look like I was running away. With the feedback of my coach and a fellow aerialist, I ended up having two variations of leg positions before ending with my legs tightly together, to ensure that the whole would not appear as if the divinity of survivors had run away. (By the way, my performance ultimately ended with my back facing the audience.)

Performance outfit

For the performance, I needed a performance outfit that would convey the chosen theme. A performance outfit for aerial acrobatics also had many functional criteria:

- Movement in the outfit must be easy and comfortable.

- The outfit must withstand special positions at the limits of mobility, sudden movements, and contact with the apparatus without the fear of revealing too much skin, for example.

- The outfit cannot have any hard or sharp parts that could damage the apparatus, which is also made of fabric.

- The outfit cannot have any extra loose fabric that could get tangled and caught on the apparatus and tear. (I have ripped many shirts by having their hem get caught on the silks.)

Within these functional constraints, however, I wanted my costume to evoke Ancient Greece and warriors of that time period. However, for functional reasons, cloak-like solutions were not an option, nor were any kind of skirts. I also did not want the outfit to look like a cheap costume, but rather I hoped that the connection to Ancient Greek warriors would be subtle. I told my coach and costume designer and seamstress that when I step onto the stage, the audience will already know my theme, but if I were in my costume somewhere else, it would not be necessary to immediately recognise the connection to Ancient Greece.

However, I also realised that the details of my outfit might not be easily visible due to the lighting and the entanglement with the apparatus. That is why I also dreamed of emphasising the theme even more with a suitable headpiece that would preferably evoke the helmets of Ancient Greek warriors. However, the possible headpiece also had strict functional criteria:

- The headpiece must stay on even when I am upside down or when I quickly turn upside down.

- The headpiece cannot have any hard or sharp parts that could damage the apparatus.

- The headpiece must be safe for me, so it cannot have any fastener under my chin, for example.

I had not yet figured out how to attach the headpiece to my head when I started to build a prototype from ordinary printing paper. My goal was to create a Minimum Viable Product: a result with as few resources as possible that would last a few performances and look credible enough in dim lighting.

The end result was made from EVA foam, which I shaped into a helmet that frames my face by glueing and sewing. The attachment was taken care of by a rubber band that goes around my head, which was secured into place with hair clips underneath the visor part. The parts that protect the sides of my face were attached to my cheeks with clothing tape. The finished “helmet” at least met all the functional criteria and stayed securely on my head throughout the performances!

More depth in storytelling with details

During the process, I constantly thought about how I could further sync my movements to the music, and on the other hand, how to link the choreography and lyrics together. Of course, I realised that the audience, who would see my performance only once, might not pay attention to all the details, but I wanted to offer something to discover for many.

It was important to me from the beginning that my performance is not just a series of tricks that I present with music playing in the background. I wanted the performance to be a thought-out whole. I wanted to compensate for the lack of impressive tricks with immersion, which was equally demanding to execute.

With immersion and the experience goals I defined in mind, I wanted to make sure that at least a few times during the performance, I would make eye contact with the audience. In practice, however, it was only about creating such a feeling for the audience, as in reality, I wouldn't have been able to look anyone truly in the eye.

I timed the eye contacts to the aforementioned lyrics “and we have arrived”, which I also emphasised with hand gestures. The end result may seem superficial, but my goal was also to offer an entertaining show, so I thought it appropriate to include potentially clichéd elements. Hand gestures also played an important role in the line “this is our time” in the song, although in these cases, I turned my gaze to where my hand was pointing.

The song also had a few lines about falling: “We're gonna watch them fall” and “the kings and queens have fallen.” Before these lines, I held the long tail of the silks hanging on my shoulder instead of letting it hang freely towards the floor, as it would typically do. When these lines came, I picked up the tail from my shoulder and let it fall. Some people who watched my rehearsals noticed the showiness of the gesture, although I don't know if they also noticed the connection to the lyrics.

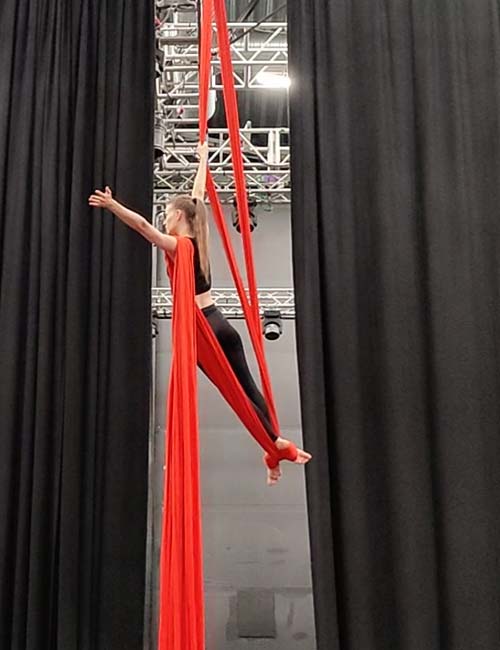

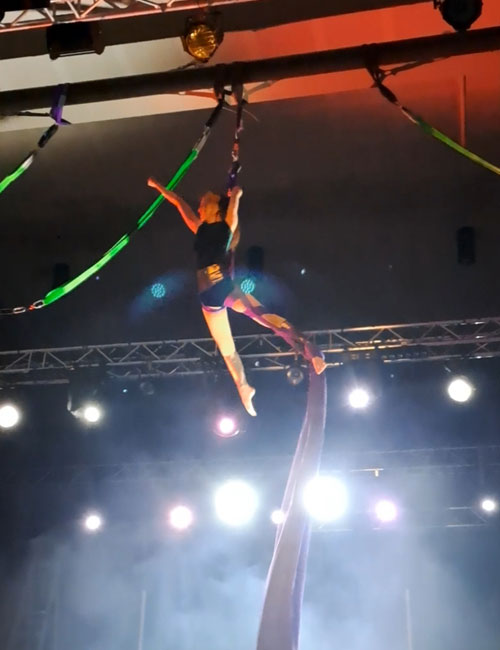

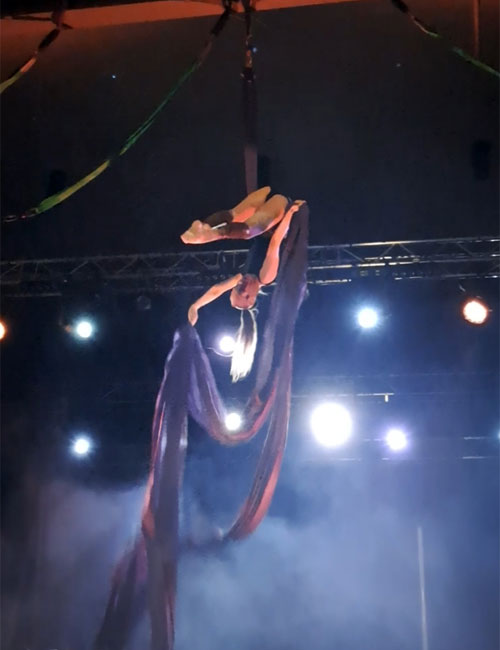

Performances

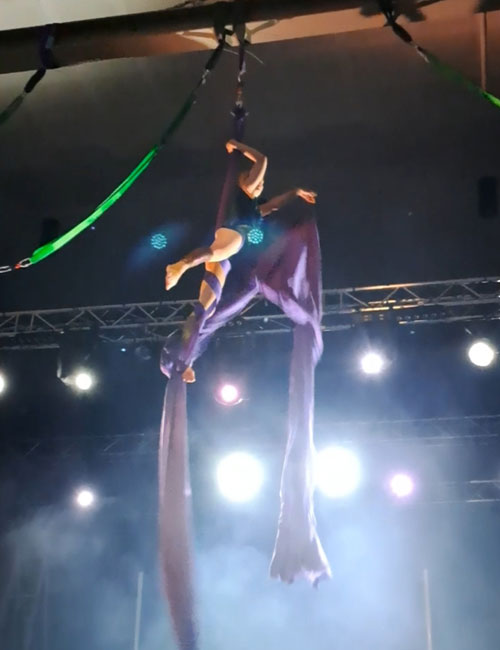

I officially presented my choreography twice: at Aerial Arts Showcase in Helsinki and at Studio Move Open Stage in Tampere. Only the first performance was recorded, and the stage and lighting were better for that performance. Video was shot by Sami Rantasalo.

Judges' feedback

At Aerial Arts Showcase, the performers received written feedback from the judges, even though it was not a competition. The feedback was spontaneous and mainly summarised what had been the most memorable aspect of the performance for the judges. Therefore, the achievement of my goals can be evaluated based on these comments, but it should be noted that the judges have also focused on critically evaluating the overall performance, rather than just enjoying it.

There were a total of six judges, all of whom were professionals or semi-professionals in pole dancing or aerial acrobatics. The comments have been translated into English as accurately as possible.

- “The costume suited the theme very well, the drop sequence was beautifully timed with the music, and the audience contact was ++. The ending was lovely!”

- “Dramatic performer, good strong and calm audience contact, musical and dynamic choreography.”

- “Wonderful expression and good stops and poses.”

- “Still need a bit more calmness in the execution, although the song and interpretation were strong, still some calmness in super gorgeous moves <3”

- “Immersive performer, strong gaze, great silhouettes.”

- “Stunning costume!”

Based on the comments, I can say that I succeeded in expression, drama, and audience contact, which were my main goals. The comment about calmness is certainly a valid critique of the technical performance and, if achieved, would not take away from the desired drama.

Although my costume was commented on twice and one judge evaluated it as fitting the theme, none of the judges specifically commented on how the tricks, music, and story related to the theme.

Evaluation of the audience experience

As I had set goals for the audience experience generated by my performance, I also wanted to evaluate it. In this context, the easiest way to collect feedback was through an online survey.

I carefully considered what I would actually ask the respondents. The survey had to be short, as otherwise, I would probably receive fewer responses. However, I also wanted to know something about the respondents, so I included a few background questions in the survey as well as two open-ended questions about the performance itself.

Regarding the performance, I asked the following questions:

- What was the most memorable thing about the performance for you?

- Describe the feelings that the performance evoked in you.

I also considered closed-ended questions, from which I could have obtained some quantitative data, but in the end, I concluded that more precise questions, possibly with answer options, might steer the respondent's attention to something that they would not otherwise have noticed. Ultimately, I wanted to receive the most unguided description of the viewer's experience, even though there was a risk that the responses would not be very long or in-depth, and I would, of course, not be able to ask follow-up questions.

I shared a link to the survey on my own social media channels, and only after my second performance, which was about two weeks after the first. Therefore, I did not collect responses immediately from the audience members who were present at Aerial Arts Showcase, even though the audience experience would have undoubtedly been at its best at the event, and their memories of the experience would have been the most reliable. As I also shared a video of my performance on my social media channels, some respondents' experiences may have been based solely on the recording.

In my background questions, I asked how or where the respondent saw my performance and whether they themselves were possibly a practitioner of aerial acrobatics or pole dance.

Nine people responded to the survey, and while I do not know exactly who the respondents are, I shared the survey link only in my own channels, so it can be assumed that the respondents know me. In theory, not all of them may be my personal acquaintances, as my Instagram account is public. However, it should be noted that some sort of personal relationship with the performer is likely to affect the experience and expectations that the viewer had beforehand. Despite this, it is unlikely that the respondents include my closest family members, from whom one would expect very uncritical admiration.

The respondents had seen my performance as follows:

- Four respondents had seen the performance at Studio Move's open stage

- Four respondents had watched the video from Aerial Arts Showcase

- One respondent had seen the performance live at Aerial Arts Showcase.

In addition, five of the respondents practise aerial acrobatics themselves, and four do not practise aerial acrobatics or pole dance at all. I will refer to the latter group as laypeople. I will take these respondent groups into account somewhat separately when analysing the responses.

Four respondents said that what stuck with them most was the immersion, body language or attitude. All of these respondents were practitioners of aerial acrobatics. On the other hand, three laypeople said that what stuck with them most was the impressive movements, and a couple of these respondents also mentioned how the movements were in sync with the music.

- “Impressive movements that emphasised the high points of the music.”

- “I particularly liked the movements and accents that matched the rhythm.”

The difference between the responses of those who practise aerial acrobatics and those who do not is interesting but not necessarily surprising. My choreography was not particularly difficult for aerial acrobatics, and respondents who practise aerial acrobatics could probably imagine performing the moves themselves. Immersion, on the other hand, is an extra element that is not usually practised in ordinary training.

The question of the emotions that the performance evoked did not clearly differentiate between the experiences of practitioners and laypeople, nor between live and recorded experiences.

Most of the respondents described their feelings as admiration, impressed, or simply “wow”. A couple of respondents also felt strong emotions that they described as follows:

- “I may have become a little emotional” (saw the performance live)

- “I got chills watching this.” (saw the performance on video)

One single response hit surprisingly close to the experience I was aiming for: “I am really bad at analysing things like this, but the performance felt uplifting, energising.” Although the wording requires interpretation, I may be able to conclude that my character created a successful connection with the audience. This is possibly supported by a couple of other comments that mentioned being “excited” and “interested”.

In both sets of responses, the music was mentioned many times. This is a pleasing result, as I put a lot of thought into selecting the music and choreography to match it.

- “Of course, the music was really powerful in creating the atmosphere, and together with the performance, it was a strong combination.”

- “The music choice fit perfectly with this.”

- “I personally wouldn't listen to that song alone, but together with the performance, it was also great.”

One of the respondents mentioned watching the video multiple times, and I have received a similar comment through sharing the video on social media. Hearing this feels rewarding after all the effort.

Outcome

The result is the culmination of almost six months of planning and practice—an aerial acrobatics performance with the theme of Alke, the embodiment of fighting spirit from Ancient Greek mythology. In addition to two live performances, many people have seen the video of the performance, and a few have even been able to watch the rehearsals.

My primary goal was to provide a powerful experience for the audience, although it was also a new experience for me. However, I didn't want to create the choreography just for myself, so I defined experiential goals and designed my performance with those in mind.

I evaluated the realisation of the audience's experience based on the answers from the survey I conducted and comments I received. I can say that I was successful to some extent in creating a memorable and emotionally engaging experience. Based on the responses, there are indications that I also succeeded in providing the specific experience I aimed for, but due to the limited number of responses, I cannot be completely sure that the desired experience was achieved exactly as I envisioned it. However, experiences are always subjective, and success cannot be guaranteed when shaping experiences. Let's count it as a success that I evoked emotions and made an impression.

Limitations

From the perspective of a systematic design and evaluation process, there are some shortcomings in the whole.

First of all, in theory, I could have received more survey responses if I had aggressively communicated my need for feedback. I could have, in principle, asked for feedback from more viewers present at Aerial Arts Showcase and immediately after the performance, but this would have required drawing more attention to myself, and I didn't really want to do that. However, for example, the opportunity to compose my own introduction before the performance would have provided a way to communicate to the audience that I wanted feedback on my performance, but I consciously left the opportunity unused—in part because stepping on stage already required enough courage, and a strange request in the introduction section would have made me stand out more from the other performers.

Because of failed rehearsals, I was afraid the performance would be a complete disaster, so I had tactically left myself the option of skipping the evaluation phase altogether if the act to be evaluated had been so terrible that I just wanted to forget it ever happened.

If I had collected feedback from the Aerial Arts Showcase audience, I might have gotten insights from people who didn't know me beforehand, so they would have had different expectations for the performance. In an ideal situation, I could also have compared how knowing the performer affects the viewer experience.

In theory, I could have involved outsiders more in the process, just like I did with the demo. However, I didn't want to burden my close circle with constant systematic feedback collection, and on the other hand, I also hoped that as many people as possible could experience the performance as it is at its best: new and surprising, presented on an actual stage. The final evaluation of the experience would probably have been different if it had been preceded by several rehearsal versions to watch and analyse.

Lessons learnt

The most important lesson of the whole process is that I can do this. Success requires systematic and persistent work - I would be lying if I claimed that I was motivated all the time. Instead, I reserved certain times for myself to go to the gym and work on the choreography, whether I was interested or not. Especially in the early stages, frustration was strong, but then I just had to repeat the familiar mantra: trust the process. When all the tricks were chosen and the training turned into choreography run-throughs, the process partially eased or at least changed its nature.

If I were to start the process again, I would probably do many things the same way as now. When necessary, I might ask for opinions more often when selecting the most suitable tricks, if there were several options in mind, but even then, the most important criterion is the tricks' suitability for artistic goals, not their subjective impressiveness factor.

Next, I will provide tips for planning a choreography from the perspective of a designer – not a professional choreographer:

- First, define your goal. The goal may be easiest to describe with adjectives, but other parts of speech and even entire sentences will do. Even if your performance is going to have a story with a classic dramatic arc, think about the emotional states that are experienced during the story.

- Once you have defined your goal, analyse what kind of movement language and individual moves or tricks are suitable for expressing your goal. Also, think about what kind of tricks at least do not express it.

- Write down your goal and your analysis. Work on these things by writing, as writing is thinking. Write and process your plans somewhere other than your training space.

- Kill your darlings. Don't fall in love with tricks and force them into places where they don't belong. When making choices, remember your goal, and be prepared to give up everything that does not promote the achievement of that goal.

- Ask for feedback, but in a way that helps you evaluate whether your work is in line with your goals. Ask viewers, for example, to guess or give their opinion on what you are trying to express. If you can't choose between several tricks, ask other people to evaluate which of your options best expresses what you are aiming for. Don't settle for others' subjective opinions on which option is the “coolest.”

- Remember that there is no perfect creative process. In practice, you always have to make compromises and proceed, even if you feel uncertain about your decisions. Don't stress whether you are following all of the above guidelines correctly or at all. Only safety issues are taken seriously, not creative activity.

Thanks

I also received invaluable help along the way, without which I might not have made it to the finish line. I want to thank my coach Sini-Susanna Paavilainen, who not only helped with improving the technical performance but also sewed my performance costume; Iina Peritalo for the conditioning exercises that supported the sport-specific training; and Vilma Lepistö for sharing the whole journey as important peer support. In addition, thanks to everyone else who gave feedback along the way. And finally, thank you to the awesome audiences and everyone who watched the video—you made it possible for me to have a fantastic experience from the performance as well.